NICE Quality Standard on the physical health of people in prison

New NICE quality standard for the physical health of people in prisons

New top-line priorities for service providers and commissioners

I was in the health care unit for a while. It was too noisy, staff had to spend all their time with the disruptive ones. Care and treatment was ok, but it depends on the prison, good and bad experiences. Seeing a doctor on main location took a while to happen, and when you are mentally ill the wait makes things worse.

Jason, 36, West Midlands

I had an injury before going into prison. It took 4 weeks to get an x-ray, and then about 5 weeks for the result, which I had to keep asking for. I’d been prescribed methadone, painkillers and anti-depressants, but it took weeks to get the right dosage, and I was put on the wrong medications – no information had been shared.

Sandeep, 36, West Midlands

Today, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has published a revised quality standard for the physical health of people in prisons, which can be found here. Quality standards are top-line, evidence-based recommendations for commissioners and providers of services, and are aimed at addressing variation in the quality and effectiveness of services. They also set clear expectations of what people in prisons should expect. These standards are particularly welcome and timely, following as they do in the wake of reports from the Inspectorate, Ombudsman and in the media, all of which have highlighted health care as one of many problems currently affecting the prison system.

The mental health of people in prison has been firmly under the spotlight recently. Report after report has highlighted not only the different ways that mental ill health can manifest in prisons, but also the difficulties that prisons and prison health services have in meeting the needs of people in what is, to be frank, a system close to breaking point. The National Audit Office found that Government wasn’t able to measure progress as it didn’t know what the level of need is – other than that it’s undoubtedly high.

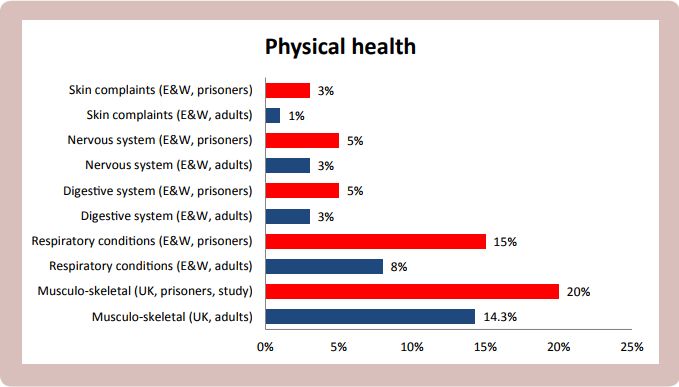

However, as we highlighted in our resource Rebalancing Act, mental ill health is just one of the difficulties that people in prison face. Often, people in prison experience, in additional to worse mental health, higher rates of physical ill health too.

This shouldn’t be that surprising – prisoners are often drawn from the most marginalised, disadvantaged and underserved parts of society and, like their peers in the community, are more likely to experience problems with substance misuse and a spectrum of health and social problems. Tuberculosis is particularly prevalent in prisons, with prevalence about 5 or 6 times higher than among the wider population. In addition to meeting direct needs, effective healthcare provision in prisons can yield rewards outside the prison gate – the ‘community dividend’.

The revised standard highlights some helpful measures:

- People entering or transferring between prisons have a medicines reconciliation carried out before their second-stage health assessment – to help ensure that people continue to receive the medicines they need and to reduce the risk of harm caused by delayed or inappropriate medication.

- People entering or transferring between prisons have a second-stage health assessment within 7 days – to explore health problems in more detail than during the initial health assessment so that people can receive the necessary treatment and support.

- People entering or transferring between prisons are tested for blood-borne viruses and assessed for risk of sexually transmitted infections – there are very high rates of blood-borne viruses in prisons, and testing means that people can receive vital support and treatment.

- People in prison who have complex health and social care needs have a lead care coordinator – so that people who are receiving care from different teams can receive joined-up care.

- People being transferred or discharged from prison are given a minimum of 7 days’ prescribed medicines or an FP10 prescription – this is to ensure that medicines can be taken consistently, maximising benefits and reducing the risk of harm.

These quality statements naturally only reflect a small part of the activity needed to provide effective healthcare in prisons, and should be implemented alongside or in light of related quality standards and guidelines, particularly NICE guideline 57, Physical health of people in prison.

HM Chief Inspector of Prisons, in his annual report argued that ‘for too many prisoners the state is failing in its duty’ to provide adequate support and care for their mental and physical health. Prisons currently face a range of difficulties, with the provision of effective healthcare being just one. Hopefully this quality standard will contribute to improving the services that people receive.

Get involved

If you’ve had experience of prison, or any other involvement in the criminal justice system, you can help to change services and systems by taking part in one of our regional forums, which meet in Birmingham, London and Manchester. See here for more information.